Sawtelle, Los Angeles

Sawtelle | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Coordinates: 34°01′50″N 118°27′48″W / 34.03056°N 118.46333°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| City | |

Sawtelle /sɔːˈtɛl/ is a neighborhood in West Los Angeles, on the Westside of Los Angeles, California. The short-lived City of Sawtelle grew around the Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, later the Sawtelle Veterans Home, and was incorporated as a city in 1899. Developed by the Pacific Land Company and named for its manager, W. E. Sawtelle, the City of Sawtelle was independent for fewer than 30 years before it was annexed by the City of Los Angeles.

Sawtelle is noted for its thriving Japanese American community, busy restaurants and arthouse movie theaters. It has strong roots in Japanese-American history. In recognition of its historical heritage, the area was designated Sawtelle Japantown in 2015.[1]

Early history

[edit]The future site of Sawtelle has been a significant location in the Los Angeles Basin for centuries, largely due to its abundant spring water. The area was originally home to the village of Kuruvungna—translated as "place where we are in the sun"—which was inhabited for thousands of years by the Tongva people, centered around the Kuruvungna Village Springs. These springs still flow today, although their natural course has been constrained by urban development, particularly in the vicinity of University High School.[2]

The first Europeans to encounter the area were Gaspar de Portolá and members of the Portolá expedition, who camped nearby in 1769.[3] Portolá's party documented a thriving community living amid lush, spring-fed terrain.[4]: 34–38

In 1839, the area that would become Sawtelle was incorporated into Rancho San Vicente y Santa Mónica, a 33,000-acre (130 km2) Mexican land grant awarded to Francisco Sepúlveda II. By 1874, the property had passed into the hands of Robert Symington Baker and John Percival Jones.[5]: 345

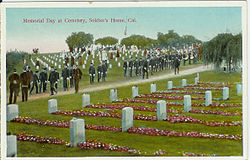

The establishment of the Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers—a federally funded old soldiers' home—in 1888 marked a turning point in the area's development. The institution expanded steadily, prompting the construction of multiple railroad lines to accommodate the growing number of residents and visitors.[6][7]

As the Pacific Branch grew, tensions arose with the neighboring city of Santa Monica. Residents there expressed concerns over the veterans’ increasing political and economic influence—particularly regarding public drunkenness and voting power. After veterans swayed the outcome of a local school board election in 1895, Santa Monica redrew its school district boundaries to exclude the soldiers’ home. Despite this, the presence of veterans receiving federal pensions continued to draw interest from real estate investors and business developers.[8]: 198–200

Founding

[edit]In 1896, the Pacific Land Company purchased a 225-acre (0.91 km2) tract of land just south of the veterans' home and hired S. H. Taft to develop a new town. The company initially sought to name the settlement "Barrett," in honor of A. W. Barrett, the manager of the veterans’ home. However, postal authorities rejected the proposal due to its similarity to Bassett. In 1899, the town was formally renamed "Sawtelle," after W. E. Sawtelle, an associate of the Pacific Land Company who later became its president in 1900.[5]: 347–349

The Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers quickly became an attraction for both tourists and real estate speculators. By 1906, it was featured as a stop on the Los Angeles Pacific Railroad’s “Balloon Route,”[9][10] a popular sightseeing circuit that transported tourists by rented streetcar from downtown Los Angeles to the coast and back.[11]

In 1905, residential lots and larger tracts were offered for sale in the new Westgate Subdivision, located adjacent to “the beautiful Soldier’s Home.” The area was owned and promoted by Jones and Baker’s Santa Monica Land and Water Company.[12] The growing community of Sawtelle developed rapidly as veterans and their families—many of whom were receiving federal pensions or other forms of assistance—settled near the Pacific Branch.[13] Much of the neighborhood’s early development occurred after the veterans’ home was established.

Annexation by Los Angeles

[edit]During the early 20th century, the City of Los Angeles expanded rapidly by annexing both incorporated and unincorporated areas of Los Angeles County, leveraging the increased water supply made possible by the newly constructed Los Angeles Aqueduct.[14]

Residents of Sawtelle began discussing annexation as early as 1913. On May 14, 1917, a vote to join Los Angeles passed—but only by a margin of three votes. The proposal was strongly opposed by Sawtelle's Board of Trustees and was quickly challenged in court by residents who argued they had not been properly informed about Los Angeles’ municipal debt obligations. While the case was still pending, the City of Los Angeles took unilateral action and staged what was widely considered a coup.[8]: 223–226

In an early morning raid in 1918, officers from the Los Angeles Police Department seized control of Sawtelle City Hall. They removed the city’s seal, financial records, and the city safe. However, the minutes of the Board of Trustees—held in the personal possession of a trustee—escaped confiscation. Despite the takeover, the Sawtelle trustees continued to meet in the City Hall chambers for two months before relocating to the home of the City Clerk in April 1918. For more than two years, Sawtelle operated as a government-in-exile, holding regular meetings and even attempting to organize local elections—efforts which ultimately proved unsuccessful.[8]: 223–226

In September 1921, the California Supreme Court ruled the annexation invalid, ending what the Los Angeles Times called “one of the longest and most bitter fights in the history of municipal governments in the State.”[15] When the Board of Trustees reclaimed City Hall on November 1, they discovered that Los Angeles officials had taken their firehoses—and most of the chairs.[16]

Despite their courtroom victory, the anti-annexation trustees were swept out of office in the next municipal election. A second referendum, held on June 2, 1922, passed overwhelmingly by a margin of over 800 votes.[8]: 223–226 Sawtelle was officially annexed by the City of Los Angeles in July 1922, becoming the 36th addition to the growing metropolis.[17]

Interwar period (1930s to 1950s)

[edit]

Sawtelle's interwar history is deeply shaped by its vibrant Japanese American community, which coalesced in response to exclusionary housing and land-use policies in other parts of Los Angeles. Many early Japanese residents settled in Sawtelle and turned to farming, often in the face of steep challenges—including denial of bank loans and restrictions imposed by the California Alien Land Law of 1913, which prohibited land ownership by non-citizens.

By 1941, Sawtelle was home to 26 garden centers, the majority of them operated by Japanese immigrants and their American-born children.[18]

These businesses were part of a much larger Japanese American presence in the neighborhood, which was dramatically disrupted during World War II, when many residents were forcibly removed and incarcerated under the policy of Japanese-American internment.[18]

The 1950s through the present day

[edit]Since the 1950s, Sawtelle has undergone significant changes, from residential redevelopment to cultural shifts. Like many parts of Los Angeles, the neighborhood has experienced periods of gang activity. The Sotel 13 gang, active since the mid-20th century, claimed Stoner Park and its surrounding community as its territory beginning in the 1950s.[19] As of 2012, gang-related graffiti was still visible in some parts of the neighborhood, though overall activity has declined substantially since the early 2000s.[20]

Geography

[edit]

The term **Sawtelle** can refer to several overlapping geographic areas: a neighborhood within the City of Los Angeles, a smaller adjacent **unincorporated area** governed by Los Angeles County, or a broader region sometimes collectively referred to as the **Sawtelle area**. In certain contexts, the name is used specifically to reference the **Veterans Administration complex**, including the modern **West Los Angeles Medical Center** and, north of Wilshire Boulevard, the historic site of the **Sawtelle Veterans Home**.

The **incorporated area** of Sawtelle refers to a 1.82-square-mile (4.7 km2) district within the City of Los Angeles. It is roughly bounded by the Interstate 405 freeway to the east, National Boulevard to the south, Centinela Avenue to the west, and Bringham Avenue, San Vicente Boulevard, and the VA grounds to the north. This area includes much of the historic Sawtelle neighborhood. The incorporated section extends approximately 1.0 mi (1.6 km) to either side of Santa Monica Boulevard, and runs westward about 1.3 miles (2.1 km) from Interstate 405 and Sawtelle Boulevard toward Santa Monica, ending at Centinela Avenue.[21]

Although this district lies within the broader region of **West Los Angeles**, its northern boundary meets Brentwood and Westwood. To the south lies the remainder of West Los Angeles, which is not generally considered part of the Sawtelle neighborhood.

In contrast, the **unincorporated Sawtelle area** is considerably smaller—576.5 acres, or 0.90 sq mi (2.3 km2)—and entirely surrounded by the City of Los Angeles. It lies near the junction of the **San Diego Freeway (I-405)** and **Santa Monica Boulevard**, and consists of seven parcels of land. Six of these are owned by the federal or state government; the seventh is owned by a private utility company. The area falls under the jurisdiction of the **Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors**, specifically within the **Third Supervisorial District**.[22]

Major facilities within this unincorporated enclave include the **Wilshire Federal Building**, the **Los Angeles National Cemetery**, the **West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (formerly Wadsworth VA Hospital)**, and several smaller federal offices.

The greater Sawtelle area spans multiple ZIP Codes, including parts of **90049**, **90064**, and **90025**, as well as the full **90073** ZIP Code—used exclusively by the **VA Medical Center** and other federal installations on the site of the original Wadsworth Hospital.

Transportation

[edit]Public transportation in Sawtelle is primarily served by Los Angeles Metro Bus, Santa Monica's Big Blue Bus, and Culver CityBus, offering regional and local connections throughout West Los Angeles.

The Metro E Line light rail runs along the southern edge of the neighborhood, with the nearby Expo/Bundy station providing access to Downtown Los Angeles, Santa Monica, and points in between.[23]

In 2027, the neighborhood will also be served by the Westwood/VA Hospital station on the D Line Extension, further enhancing connections to Koreatown, Downtown Los Angeles, and the expanding Metro rail system.[24]

Sawtelle participates in the Los Angeles Department of Transportation’s **Slow Streets program**, which aims to reduce through-traffic and reclaim road space for pedestrians, cyclists, joggers, children, and people with disabilities. The initiative was introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic and continues in select corridors.[25]

In 2017, Sawtelle was named one of **Los Angeles's 10 most walkable neighborhoods**, recognized for its pedestrian-friendly design, density of amenities, and proximity to transit.[26]

Sawtelle Boulevard serves as a major arterial road and is widely considered the cultural and commercial heart of the Japanese American community in West Los Angeles.[27] Other major thoroughfares in the neighborhood include Santa Monica Boulevard and Olympic Boulevard. The neighborhood is directly accessible via the Santa Monica Freeway (I-10) and the San Diego Freeway (I-405).

Arts and culture

[edit]Sawtelle is home to two independent arthouse movie theaters that are significant institutions within the Los Angeles film community. The Nuart Theatre, built in 1929, regularly showcases domestic and international independent films and is known for its long-running midnight movie screenings, including cult classics like The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

The Laemmle Royal Theatre, originally opened as the Tivoli in 1924, is one of Southern California’s last remaining single-screen theaters in continuous daily operation.

The Village recording studio, located on Butler Avenue, has hosted numerous renowned artists. Notable albums recorded there include Steely Dan’s Aja, Frank Zappa’s Joe’s Garage, and Bob Dylan’s Planet Waves. The studio has also been used for recording major film and television soundtracks, including O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Toy Story 2, Walk the Line, The X-Files, WALL-E, and The Shawshank Redemption. A prominent mural decorates its south-facing wall.

The Japanese Institute of Sawtelle, located on Corinth Avenue at the southern edge of the neighborhood, serves as a cultural center for the West Los Angeles Nikkei community.[28]

Stoner Park functions as a central community hub and features tennis courts, a children’s playground, a skate plaza, a seasonal outdoor pool, a recreation center, and a Japanese garden. The park is located at the northern end of Stoner Avenue.

Education

[edit]

Public schools

Sawtelle is part of the Los Angeles Unified School District.

These elementary schools serve the incorporated Sawtelle area:[citation needed]

- Brockton Avenue Elementary School

- Richland Avenue Elementary School

- Nora Sterry Elementary School

- Westwood Elementary School (in Westwood)[citation needed]

-

Daniel Webster Middle School

-

Richland Avenue Elementary School

-

Nora Sterry Elementary School

-

Brockton Avenue Elementary School

These middle schools serve the Sawtelle area:

- Daniel Webster Middle School

- Emerson Middle School (in Westwood)[citation needed]

The Sawtelle area is within the University High School attendance district.[29]

Private schools[30]

- Arete Preparatory Academy

- Brawerman Elementary School

- New Horizon School

- New Roads Elementary School

- Park Century School

- Saint Sebastian School

- Southern California Montessori School

- Wildwood School

Asahi Gakuen, a weekend Japanese supplementary school, operates its Santa Monica campus (サンタモニカ校・高等部, Santamonika-kō kōtōbu) at Daniel Webster Middle School in Sawtelle. At one time, all high school classes in the Asahi Gakuen system were held at this campus.[31][32] In 1986, students took buses from as far as Orange County to attend high school classes here.[33] As of 2024, Asahi Gakuen’s Santa Monica, Orange, and Torrance campuses host high school classes.[34]

Veterans Administration hospital, office buildings, and national cemetery

[edit]

The grounds of the former Sawtelle Veterans Home, established in 1888 alongside a hospital and cemetery for former soldiers and sailors, are also referred to as Sawtelle. This area—home to historical buildings, former apartments, and now primarily research and office facilities—lies mostly north of Wilshire Boulevard. Since 1977, the site has formally included the Veterans Affairs (VA) Wadsworth Medical Center (now the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center),[35] which sits south of Wilshire Boulevard, across from the original veterans' home site. This facility is a key component of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

The hospital and veterans’ home campus are located west of the Interstate 405 freeway (San Diego Freeway), which now bisects this historic federal parcel. In the 1960s, a controversial proposal sought to exchange the site for Hazard Park in Boyle Heights, which would become the location for a new VA hospital. The plan sparked fierce public opposition and was ultimately abandoned after seven years.[36][37] Instead, the current West Los Angeles Medical Center was constructed and opened in 1977.

The Los Angeles National Cemetery, located east of the 405 freeway between Sepulveda Boulevard and Veteran Avenue, contains the remains of more than 85,000 veterans and family members, spanning from the Mexican-American War to the present day. Adjacent to the cemetery and just south of Wilshire Boulevard is the Wilshire Federal Building, a prominent federal office complex often misidentified as being located in Westwood.

Wilshire Federal Building

[edit]A major stand-alone federal office building in the area is the 19-story Wilshire Federal Building[38], completed in 1969 and located at 11000 Wilshire Boulevard in the unincorporated Sawtelle area (often misattributed to Westwood).

The building is one of the most visible symbols of federal presence in the Los Angeles region and has become a frequent location for demonstrations, rallies, and protests against government policies.

It also houses the Los Angeles FBI field office, among other federal agencies.[39]

Demographics

[edit]From the 1980 U.S. Census to the 1990 U.S. Census, an increase in construction caused the population to rise by 6.7%; the addition of 692 dwelling units increased the housing stock in Sawtelle by 10.6%. The 1990 census recorded 14,042 residents in Sawtelle. There was no racial majority at that time. Barbara Koh of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "The racial percentages in Sawtelle in the 1990 Census were virtually unchanged from 1980." [40]

According to the 1990 census data:

- 48% of residents were Non-Hispanic White

- 26% were Latino or Hispanic

- 23% were Asian

- 3% were Black [40]

According to 2005 Los Angeles County government estimates, the population of the unincorporated area of Sawtelle was 634. [41]

These numbers only tell part of the story. Sawtelle's demographic evolution has long reflected the broader tensions and transformations of West Los Angeles — from its early roots as a haven for Japanese American families facing exclusion elsewhere, to the impacts of postwar housing booms and gentrification. Despite waves of change, the neighborhood has retained its distinctive character through a strong sense of community, cultural continuity, and civic engagement. [42]

Public services

[edit]The Los Angeles Police Department operates the West Los Angeles Community Police Station at 1663 Butler Avenue, 90025.[43]

The Los Angeles Fire Department's Station 59, located at 11505 West Olympic Boulevard, provides fire protection for Sawtelle and surrounding areas. In the LAFD's command structure, it is organized in the West Bureau.[44]

The West Los Angeles Regional Branch Library, a branch of the Los Angeles Public Library, is located at 11360 Santa Monica Boulevard.[45]

The Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety (LADBS) maintains a Development Services Center at 1828 Sawtelle Boulevard, 2nd Floor, offering services such as express permits and plan checks.[46]

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services (DPSS) operates a district office at 11110 W. Pico Boulevard, providing assistance programs including CalWORKs, CalFresh, and Medi-Cal to eligible residents.[47]

The Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering's West Los Angeles District Office is located at 1828 Sawtelle Boulevard, 3rd Floor, handling public infrastructure projects and services in the area.[48]

In fiction and popular culture

[edit]- Neal Stephenson's science fiction novel Snow Crash coins the name Fedland for the unincorporated Sawtelle area, as one of the last remnants of federal territory in a privatized future America. In the book, the area remains under direct federal control, while most of the rest of the country has been absorbed by corporate franchises.[citation needed]

- Director Michel Gondry filmed part of Beck's video for "Deadweight" at the Nuart Theatre, a landmark of Sawtelle's arthouse cinema scene.

- University High School's close proximity to Hollywood studios has made it a frequent filming location for film and television. Notable productions shot there include Bruce Almighty, Pineapple Express, Valentine's Day, Straight Outta Compton, and the television series Arrested Development.

- Khalid filmed the music video for his breakout single "Young Dumb & Broke" at University High School, highlighting the school's aesthetic and pop culture cachet. Janelle Monáe also shot parts of her "Tightrope" video there.

- John Waters filmed a "No Smoking" PSA trailer for theatrical projection at the Nuart Theatre, in which he sarcastically encouraged patrons to "smoke anyway," cementing the Nuart's reputation for subversive cinematic culture.

- The 1992 film Article 99, a black comedy-drama centered on systemic neglect and corruption within a VA hospital, was originally slated to screen at the Wadsworth Theatre, located on the VA grounds. The screening was quietly blocked, allegedly for psychiatric concerns, though many veterans and activists believe the true reason was to avoid drawing attention to real-life land misuse and institutional failures at the West Los Angeles VA campus.

- The VA campus itself has been used as a filming location by various production companies, including commercial shoots and television series. Some of these arrangements later became subjects of legal scrutiny and class action lawsuits, with veterans and advocacy groups citing misuse of land intended exclusively for veterans' housing and healthcare. This was one of the catalysts that led to the Veterans Row protest along San Vicente Boulevard.

- Veterans Row, while not fictional, has taken on symbolic weight in public consciousness. The encampment, formed by unhoused veterans outside the West LA VA campus during the COVID-19 pandemic, became a nationally visible protest against decades of failed land use, broken promises, and neglect. Though not yet depicted in popular media, Veterans Row continues to inspire documentaries, podcast coverage, and planned film projects focused on housing justice and government accountability.

See also

[edit]- Sawtelle Line

- History of the Japanese in Los Angeles

- Stephen W. Cunningham – Los Angeles City Council member who blocked public housing in Sawtelle

- Veterans Row – Protest encampment on the grounds of the West Los Angeles VA campus

- Valentini v. Shinseki – Landmark class-action lawsuit regarding VA land misuse

- West Los Angeles VA Medical Center

- Wadsworth Theatre

- Los Angeles National Cemetery

References

[edit]- ^ Hirahara, Naomi (April 15, 2015). "Thinking L.A.: How West L.A. became a haven for Japanese-Americans". UCLA Newsroom. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ "Kuruvungna Village Springs: History". Gabrielino-Tongva Springs Foundation. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ Hamilton, Denise (March 30, 2020). "The Secret Sacred Spring in West L.A." Alta. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ Zachary, Brian Curtis (August 2007). The enduring evolution of Kuruvungna: A place where we are in the sun (M.H.P. thesis). University of Southern California.

- ^ a b Ingersoll, Luther A. (1908). Ingersoll's Century History, Santa Monica Bay Cities. Los Angeles: L.A. Ingersoll. LCCN 10014107. Retrieved 2024-02-23 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Pacific Branch: Los Angeles, California". National Park Service. November 21, 2017. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ "History". VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare. November 8, 2023. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson, Cheryl L. (2013). "The Soldiers' City: Sawtelle, California, 1897–1922". Southern California Quarterly. 95 (2): 188–226. doi:10.1525/scq.2013.95.2.188.

- ^ Pacific Electric Westgate Line

- ^ Pacific Electric Santa Monica Air Line

- ^ Wadsworth Chapel

- ^ Loomis, Jan (2008). Brentwood. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5621-5.

- ^ Robbing Veterans of Pension 1904

- ^ Wedner, Diane (December 17, 2006). "A coup that stuck". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ "Sawtelle Ready, Anxious to Join City". Los Angeles Times. November 27, 1913. Cited in Wilkinson 2013, p. 224

- ^ Garrigues, George (January 27, 1963). "EARLY MORNING COUP BY LOS ANGELES: Police Seizure of City Hall Starts Sawtelle on Exit Path". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Annexation and Detachment Map" (PDF). City of Los Angeles. August 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26.

- ^ a b Okazaki, Manami (November 4, 2017). "Sawtelle Japantown: A return to one's roots?". The Japan Times.

- ^ Romero, Dennis (November 6, 2003). "Gangster's Paradise Lost". Los Angeles City Beat. Archived from the original on 2006-10-20.

- ^ Romero, Dennis (January 4, 2012). "David Morales: Sawtelle Shooting Takes Life, Injures Another in West L.A." LAWeekly. Archived from the original on 2013-11-04.

- ^ [1] Incorporated Sawtelle boundaries are shown

- ^ Sawtelle Zoning Study, Los Angeles County

- ^ Central LA/Westside Bus & Rail Service (Map). Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. December 2023.

- ^ Nelson, Laura J. (February 12, 2020). "Metro secures $1.3 billion to finish the Purple Line subway to West L.A." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- ^ Fonseca, Ryan (May 22, 2020). "LA's Slow Streets Program Is Picking Up Speed (Despite Some Attacks On Signs)". LAist. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- ^ Chiland, Elijah (September 19, 2017). "LA's 10 most walkable neighborhoods". Curbed LA. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- ^ Groves, Martha (March 28, 2015). "West L.A. neighborhood to be recognized as 'Sawtelle Japantown'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ "A Legacy To Honor, A Future To Build: The Japanese Institute of Sawtelle Renovation Plan 2021" (PDF). Japanese Institute of Sawtelle. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-01-04. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ "Pacific Palisades High School Attendance Zone" (PDF). Palisades Charter High School. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- ^ "Mapping L.A.: Sawtelle Schools". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "サンタモニカ校・高等部." Asahi Gakuen. Retrieved on March 30, 2014. "DANIEL WEBSTER MIDDLE SCHOOL 11330 W. Graham Place, Los Angeles, CA 90064"

- ^ "Mapping L.A.: Sawtelle". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (November 13, 1986). "'School of the Rising Sun' : Surroundings Are American but Classes, Traditions Are Strictly Japanese". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2020-08-11. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ "Asahi Gakuen: About Us" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-10-31. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ "Wadsworth VA website". Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ "Victory for Save Hazard Park Assn". Los Angeles Times. September 5, 1969. p. C6.

- ^ "Hazard Park Swap Foes Stage Protest". Los Angeles Times. March 6, 1967. p. E7.

- ^ "Wilshire Federal Building". SkyscraperPage. Retrieved 2025-04-13.

- ^ "Los Angeles Division". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 2025-04-13.

- ^ a b Koh, Barbara (July 7, 1991). "Old-timers lament as nurseries and duplexes give way to pricey condos, making the ethnic neighborhood into just another part of West L.A." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ "Los Angeles County, unincorporated population estimates (2005)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "Sawtelle Japantown Report #1" (PDF). UCLA Asian American Studies Center. Retrieved 2025-04-14.

- ^ "West Los Angeles Community Police Station". Los Angeles Police Department. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ "Find Your Station". Los Angeles Fire Department. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ "West Los Angeles Regional Branch Library". Los Angeles Public Library. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ "West LA - LADBS". Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety. Retrieved 2025-04-14.

- ^ "Department of Public Social Services - LA County". Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services. Retrieved 2025-04-14.

- ^ "Office Locations - West Los Angeles District Office". Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering. Retrieved 2025-04-14.

Further reading

[edit]- Fujimoto, Jack (2007). Sawtelle: West Los Angeles's Japantown. Images of America. Japanese Institute of Sawtelle, Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-4797-8.

External links

[edit]- Sawtelle, Los Angeles

- Neighborhoods in Los Angeles

- Former municipalities in California

- Japanese-American culture in California

- Unincorporated communities in Los Angeles County, California

- Westside (Los Angeles County)

- Populated places established in 1896

- 1896 establishments in California

- Unincorporated communities in California